Bread in ancient Rome

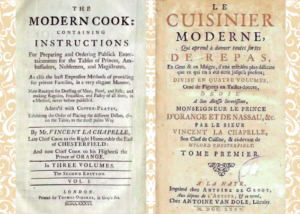

Du pain des origines au corpus pistorum

Du croustillant panis quadratus aux galettes sèches des soldats, le pain accompagne l’histoire romaine comme un fil de farine et de feu. Aliment essentiel et objet de culte, il traverse les classes sociales et les usages, dans une diversité étonnante qui dans une diversité étonnante qui reflète la richesse de la culture romaine.

Des galettes primitives à la fermentation

Les premières formes de pain apparaissent dès le Néolithique, sous la forme de galettes plates non levées préparées à partir de céréales comme le millet et l’orge. Ces grains étaient broyés avec des pierres et mélangés à de l’eau pour former une pâte cuite sur des pierres chaudes ou dans des cavités chauffées.

La fermentation fut probablement découverte par hasard, lorsqu’une pâte se mit à lever naturellement., donnant un pain plus léger, plus savoureux et plus digeste. Dès lors, la panification prit un nouvel essor, et le pain devint un aliment apprécié non seulement pour ses qualités nutritives mais aussi pour sa meilleure conservation.

Les techniques les plus simples, comme la cuisson sur la pierre ou sous des cloches en argile, allaient coexister longtemps avec les fours plus élaborés, qui deviendraient un symbole de maîtrise technique dans les sociétés antiques.

De l’Égypte à Rome : savoir-faire et adoption

Les Égyptiens maîtrisaient déjà la panification, comme le montrent les fresques funéraires où l’on voit moudre le grain, pétrir la pâte et cuire le pain. Leur pain, souvent rond, était obtenu grâce à des fours spécifiques.

Ces savoir-faire se transmirent aux autres civilisations méditerranéennes et arrivèrent à Rome par l’intermédiaire des Grecs. Pline l’Ancien rapporte que les Romains commencèrent à fabriquer du pain fermenté seulement à partir du IIIᵉ siècle av. J.-C., auparavant ils se contentaient de galettes simples.

Une fois adopté, le pain se diffusa rapidement dans toutes les couches de la société romaine. Les textes et les représentations antiques confirment son rôle central, des repas familiaux aux festins publics, et son intégration dans la culture quotidienne.

Une diversité de pains pour tous les goûts

Les Romains ne se contentaient pas d’un seul type de pain. Au contraire, ils en connaissaient plus de trente variétés, adaptées aux classes sociales, aux usages, ou même à des régimes particuliers. Ainsi, le panis siligeneus, blanc et raffiné, était réservé aux élites, tandis que le cibarius, sombre et rustique, nourrissait le peuple. Le furfureus, composé de son, était considéré comme le plus grossier, et le panis candidus, d’un blanc éclatant, passait pour un luxe raffiné. À côté de ces pains quotidiens, on trouvait le parthicus, réputé pour sa mie spongieuse, ou encore le panis adipatus, enrichi de lard.

Certains pains répondaient à des usages spécifiques : le pepsianus, plus digeste, était destiné aux malades ; le bucellatus s’apparentait à un pain biscotté, idéal pour la conservation. D’autres, comme le strepiticus, se rapprochaient d’une pizza primitive à base de farine, eau, huile, saindoux et poivre. Le testicius, quant à lui, était l’ancêtre de la piadina romagnole, préparé et consommé par les soldats en campagne.

Enfin, certains pains se distinguaient par leur fonction symbolique ou festive : le panis ostrearius accompagnait les huîtres, l’ortolaganus se préparait pour les célébrations avec légumes, fruits confits, miel, huile et vin. Lors des spectacles, on lançait au public des missilia, petits pains jetés depuis les gradins.

Parmi tous, le plus emblématique reste le panis quadratus : une miche incisée en huit quartiers, parfois entourée d’une cordelette pour la cuisson. Des exemplaires carbonisés en ont été retrouvés à Pompéi, figés par l’éruption du Vésuve en 79 apr. J.-C. Ce pain est devenu l’image la plus célèbre de la panification romaine, symbole tangible du quotidien d’il y a deux millénaires.

Fournils, corporations et symboles

Les boulangeries romaines, appelées pistrina, produisaient en quantité pour les villes. On y trouvait des meules, des pétrins et de grands fours. Les boulangers étaient regroupés dans le corpus pistorum, une corporation active dès le IIᵉ siècle av. J.-C.

Malgré cela, beaucoup de familles continuaient à préparer leur propre panis artopticus. Le pain pouvait avait aussi une valeur symbolique et certaines croyances recommandaient de ne pas le couper avec un couteau.

Mais au-delà de son rôle alimentaire et social, le pain avait aussi une dimension sacrée. Les Romains plaçaient chaque étape de la culture du blé sous la protection des divinités : la graine protégée par Seia, la moisson confiée à Runcina, la floraison placée sous l’œil de Flora, et la maturation guidée par Matuta. Offert aux dieux lors des rites et des fêtes, le pain dépassait ainsi la simple nourriture : il devenait un lien entre les hommes et le divin, un geste d’harmonie et de gratitude envers les forces de la nature.

Aliment quotidien, marqueur social et objet symbolique, le pain dans l’Antiquité romaine illustre l’ingéniosité et la richesse culturelle de cette civilisation. Chaque fournée raconte une histoire, mêlant traditions héritées, innovations techniques et rituels partagés.

Find other blog articles

Find other blog articles