La fourchette

De Byzance à Versailles, l’itinéraire tumultueux d’un geste raffiné

Avant d’être si familière à nos mains, la fourchette fut longuement boudée, jugée inutile, arrogante, voire immorale. Son chemin vers la table occidentale, de Byzance à Versailles, fut semé de soupçons, de résistances et de transformations. Car adopter cet ustensile, c’était aussi changer son rapport au corps, à la nourriture… et au monde.

De Byzance à Venise : l’ustensile qui scandalise

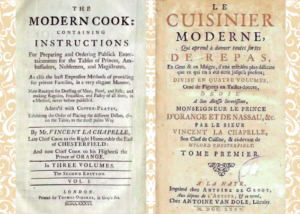

C’est au XIe siècle qu’a lieu le premier scandale retentissant autour de la fourchette. Une princesse byzantine, Maria Argyropoula, issue d’une illustre lignée impériale, épouse le fils du doge de Venise. Lors de leur fastueux banquet de noces, elle s’attire les foudres du clergé en utilisant une fourchette en or à deux dents pour porter les aliments à sa bouche.

Un prédicateur vénitien s’en émeut publiquement : « Dieu, dans sa sagesse, a donné à l’homme des fourchettes naturelles : ses doigts. » L’usage d’un objet métallique entre la main et la bouche était perçu comme un affront à l’ordre divin. Pire encore, la ressemblance troublante avec la fourche du Diable nourrissait les soupçons religieux. Pour certains moines, cette pratique relevait de la vanité, voire de la damnation. Manger avec une fourchette devenait un acte de rupture symbolique : contre la tradition, contre la simplicité, contre Dieu lui-même.

L’Italie, entre raffinement et rejet

En Italie, la fourchette poursuit son lent chemin au XIIIe siècle. Les grandes cités de la péninsule – Venise, Florence, Naples – s’en font les ambassadrices discrètes. Dans ces milieux raffinés, l’art culinaire se sophistique : sauces délicates, fruits en sirop, douceurs sucrées… La fourchette à deux dents, parfois en or ou en corne ouvragée, permet une dégustation plus élégante.

Mais l’objet reste cantonné aux tables les plus aristocratiques. Le clergé continue de lui opposer une morale de la simplicité, valorisant la proximité des doigts avec l’aliment, comme au temps du Christ. Manger à la main, c’est toucher le sacré. La fourchette, en contraste, devient un symbole d’ostentation, un signe d’une élite en quête de distinction.

Quant à Catherine de Médicis, souvent citée comme celle qui aurait introduit la fourchette en France au XVIe siècle, elle semble avoir surtout renforcé un usage déjà existant dans certains milieux de cour. Par ses banquets et sa culture florentine, elle a contribué à faire de cet objet un emblème de raffinement, sans pour autant l’imposer au quotidien.

En France, le long apprentissage d’un geste nouveau

En France, les fourchettes apparaissent dans les inventaires royaux dès le XIVe siècle. Jeanne d’Évreux et Charles V en possédaient, mais leur usage restait limité aux fruits confits ou aux mets collants. En 1574, une fourchette à deux dents figure parmi les trésors royaux, réservée à la dégustation des poires cuites. À la cour des Valois, certaines fourchettes à trois dents deviennent des objets de mode, associées à une esthétique nouvelle du geste.

Toutefois, le repas demeure un moment tactile, partagé, structuré par le pain, les doigts, la proximité physique. Introduire une fourchette suppose de repenser ce rapport au corps, de contrôler ses mouvements, d’adopter un nouveau rituel. Louis XIV lui-même préférait manger avec les doigts, qu’il essuyait sur une serviette humide après chaque plat. À Versailles, la hiérarchie des services dominait celle des ustensiles.

Mais les mentalités changent. Les philosophes des Lumières, sensibles aux idées de mesure, de contrôle et d’hygiène, promeuvent l’usage de la fourchette comme geste civilisé. Dans les salons parisiens, elle devient un marqueur de distinction, un signe discret de maîtrise de soi, à l’opposé des pulsions instinctives.

De l’objet rare au symbole de civilisation

Ce qui fit la fortune de la fourchette, ce n’est pas tant son utilité que sa valeur symbolique. Trois dents, puis quatre dents à partir de la fin du XVIIIe siècle, un manche plus long, une fabrication plus soignée : elle s’adapte aux goûts d’une bourgeoisie montante en quête de codes sociaux.

L’Église, jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle, voit encore en elle un instrument de tentation, de gourmandise excessive. Mais les manuels de civilité l’intègrent peu à peu dans les règles du bien-vivre. Elle devient un outil d’éducation : porter les aliments avec précision, en silence, les poignets près du corps. Chaque geste à table devient un signal d’appartenance sociale.

La Révolution française puis le XIXe siècle démocratisent ces usages. La fourchette quitte les palais pour les intérieurs bourgeois, puis populaires. Elle incarne une société où l’espace individuel remplace la table partagée, où les ustensiles définissent la manière de se tenir. Elle marque aussi la séparation entre l’homme et son aliment, entre nature et culture, entre instinct et bienséance.

Longtemps jugée superflue, la fourchette a bouleversé nos manières sans bruit. Derrière ce simple objet d’acier ou d’argent se cache une lente conquête : celle de la retenue sur l’élan, du raffinement sur l’instinct. Chaque époque l’a façonnée à son image, entre sacrilège, mode et civilité. En s’invitant à table, elle n’a pas seulement changé notre façon de manger — elle a sculpté un art de vivre.

Find other blog articles

Find other blog articles