Quand Paris mit le couvert

Le nouveau théâtre du goût

Avant de devenir une habitude, le restaurant fut une révolution. Dans le Paris du XVIIIᵉ siècle, il surgit comme un objet social non identifié : ni auberge, ni table d’hôte, ni traiteur, mais un lieu nouveau, à mi-chemin entre soin du corps et mise en scène de soi. Cette innovation française, longtemps ignorée de l’histoire culinaire, a pourtant changé notre manière de manger, de nous montrer, et de vivre.

Le bouillon et la santé

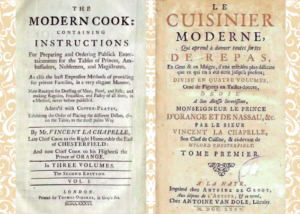

Tout commence en 1765, à Paris, quand Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau ouvre un établissement singulier, d’abord rue des Poulies, puis transféré à l’Hôtel d’Aligre, rue Saint-Honoré. Sur la façade figure une devise latine pastichant un verset de l’Évangile selon Matthieu : « Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis, et ego vos restaurabo » — « Venez à moi, vous dont l’estomac souffre, et je vous restaurerai. »

Ce lieu, qu’il nomme « Maison de santé », propose des bouillons fortifiants appelés « restaurants », servis à toute heure, dans le calme, à des clients installés seuls. Loin du brouhaha des tables d’hôtes ou des auberges, l’espace favorise le confort, la discrétion, le soin de soi.

Longtemps, certains ont attribué cette innovation à un mystérieux « Boulanger », mais les recherches contemporaines — notamment celles de l’historienne Rebecca Spang — n’ont retrouvé aucune trace fiable de ce personnage. Il s’agirait, selon elle, d’un surnom ou d’une confusion avec Roze de Chantoiseau lui-même.

La véritable révolution n’est donc pas tant dans le bouillon que dans cette nouvelle façon de manger en ville : seul, libre, à son rythme. Le restaurant moderne est né.

La carte de ses envies

Très vite, la vocation médicinale du lieu cède le pas à une forme de restauration plus large. L’idée d’un bouillon fortifiant devient le point de départ d’une offre nouvelle, plus raffinée, plus libre, plus séduisante. Roze n’est pas seulement un marchand de santé : il pressent que manger peut aussi être un art de vivre.

Chez Roze, on ne mange pas à heure fixe à une table d’hôte, en compagnie d’inconnus. On choisit son plat, son horaire, et l’on s’installe dans un cabinet particulier, seul ou accompagné. Le repas devient un moment intime, choisi, parfois mondain — mais toujours à sa propre mesure. Cette possibilité de manger « à la carte », alors que tout le monde est encore habitué au menu fixe, est révolutionnaire. L’ordinaire devient exceptionnel. Le client est libre, servi avec discrétion, et paie cher pour cela : une livre par repas, parfois plus. Ce n’est pas la cuisine qui attire mais le cérémonial et le confort.

Le restaurant, ainsi conçu, n’est pas un lieu de simple subsistance : c’est un espace de représentation sociale. On s’y montre, on s’y isole, on y choisit ce qu’on expose. L’Ancien Régime y perçoit une menace ; les Lumières, une promesse.

Le théâtre du goût

Les tout premiers restaurants sont fréquentés par une clientèle très choisie. Pas encore les bourgeois pressés, mais plutôt des aristocrates déclassés, des rentiers cultivés, des lettrés à la recherche d’un entre-soi à la fois discret et raffiné. Le menu imprimé, présenté comme un objet de lecture, devient à lui seul une promesse d’évasion.

On s’y rend aussi pour lire, observer, rencontrer, sans la contrainte de l’auberge ou de la domesticité. Le mobilier se raffine, l’éclairage se travaille, la vaisselle s’harmonise.

Le restaurant devient un « théâtre du goût », au sens plein : mise en scène de soi, décor choisi, public invisible mais présent.

Et dans ce monde où le paraître s’écrit sur une nappe immaculée, la nourriture n’est plus un prétexte : elle devient sujet. D’ailleurs, de nouveaux critiques s’en emparent, à commencer par un certain Grimod de La Reynière.

Grimod, le gastronome en scène

Avec Grimod de La Reynière, le restaurant entre dans la littérature. Ce fils de fermier général, né en 1758, érudit fantasque aux mains malformées qu’il cache sous des gants, invente un nouveau genre : la critique gastronomique. Son « Almanach des gourmands » (1803–1812) devient la bible d’une société où l’on juge les plats comme on commente les spectacles.

Chaque mercredi, dans son hôtel particulier puis au Rocher de Cancale, il organise des dîners-jurys. Les restaurateurs y envoient leurs plats, jugés à l’aveugle. Les meilleurs gagnent une place dans l’Almanach, les autres une critique parfois assassine. Grimod, avec esprit, calembours et comparaisons picturales, érige la gastronomie en art. Pour lui, le turbot est le faisan de la mer, la sardine l’ortolan du pauvre.

Il introduit surtout un nouveau rapport à la nourriture : subjective, esthétique, sociale. À travers ses mots, c’est tout un art de vivre à la française qui prend forme. Et le restaurant devient le véritable théâtre de cette nouvelle comédie humaine.

Lieu de soin devenu salon, le restaurant à la française est né de ce croisement unique entre confort, sociabilité, goût et mise en scène. En quelques décennies, il a transformé l’acte de se nourrir en expérience esthétique, intellectuelle et sociale. Plus qu’une invention parisienne, il est devenu une scène du monde.

Find other blog articles

Find other blog articles